When we talk about rigor in math education, we all recognize that it’s something we strive for in our classrooms. But rigor is often misunderstood. Ask a group of educators to define it, and you’ll likely hear a range of responses—some equate it with complex computation, others with challenging content, and some with making math class “hard.”

Yet, if our goal is to foster deep mathematical understanding, we must reconsider what rigor truly means. It’s not just about pushing students through increasingly difficult calculations or going “fast” in progression of content—it’s about developing a deep, authentic command of mathematical concepts. This includes procedural fluency, conceptual understanding, and the ability to apply math in meaningful ways.

So how do we achieve this? How do we create a rigorous math classroom that challenges students without simply making the numbers bigger?

Rethinking Rigor: Beyond Computation

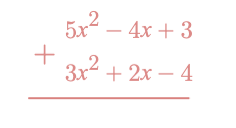

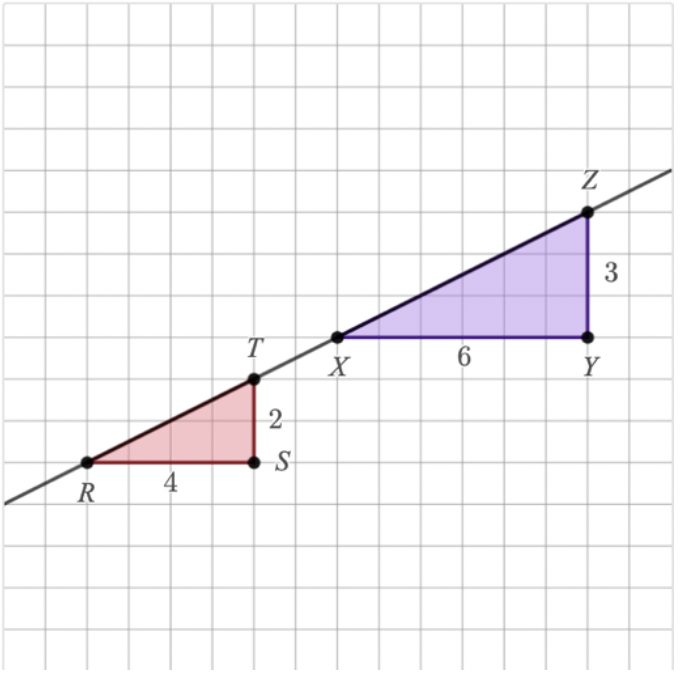

A common approach to increasing rigor is to increase the difficulty of arithmetic problems. For example, students may start with adding single-digit numbers, then progress to double-digit sums, which introduces the concept of carrying or starting with adding fractions with numerators smaller than denominators and then moving to include improper fractions. While computational rigor is one aspect of mathematical fluency, it’s only a small piece of the puzzle. True rigor comes from engaging students in deeper thinking, problem-solving, and reasoning.

Instead of just making problems harder through computation, we can increase rigor by focusing on three strategies:

- Creating Mathematical Conflict: Break Something

- Building Meaningful Connections

- Empowering Students as Mathematical Creators

1. Creating Mathematical Conflict: Break Something

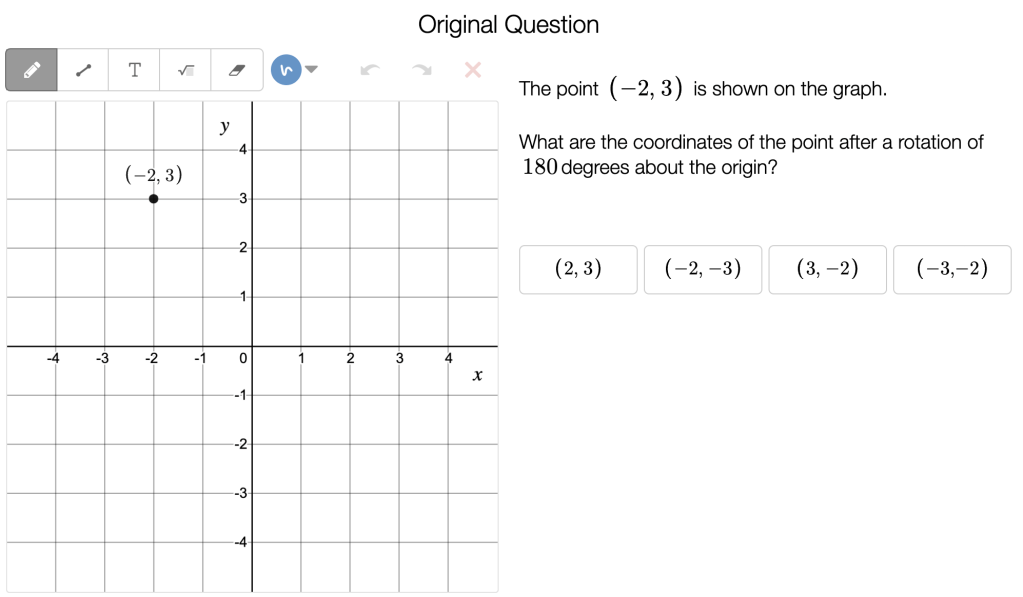

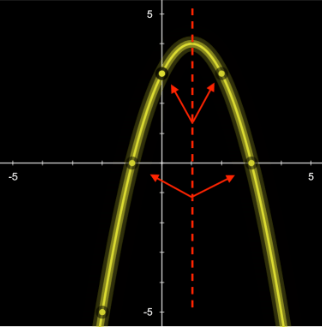

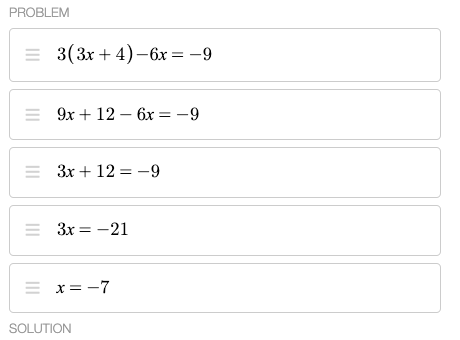

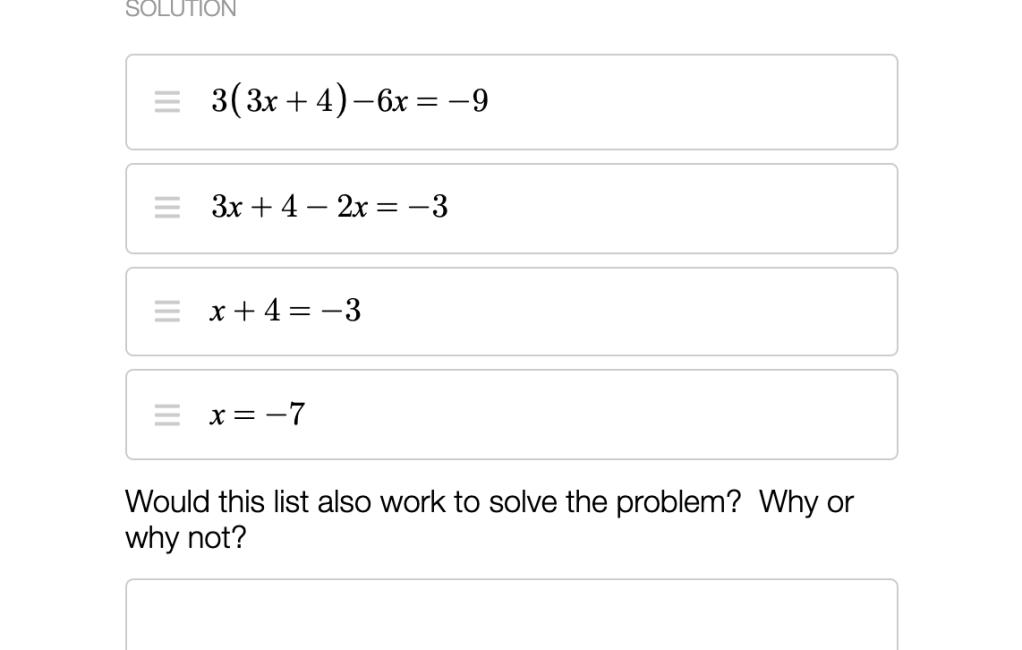

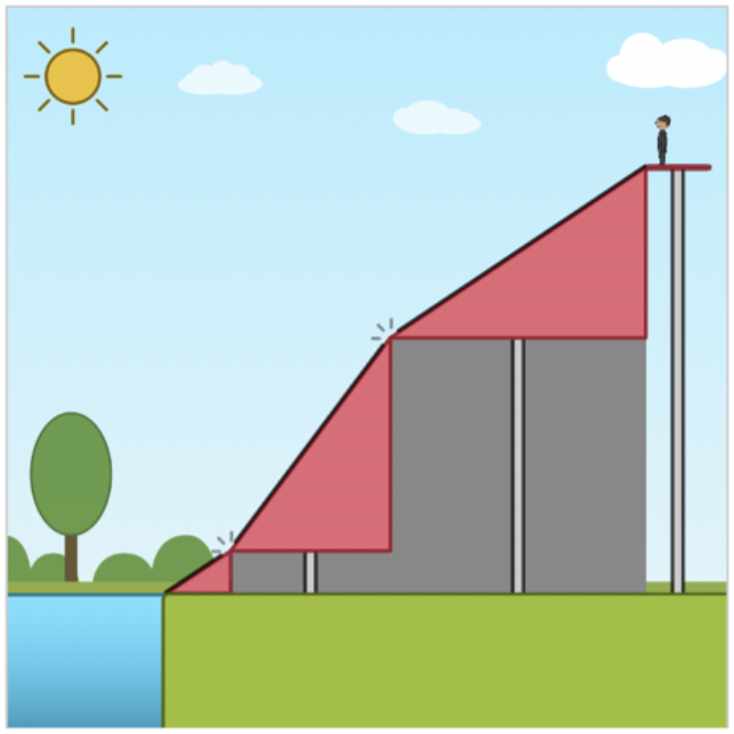

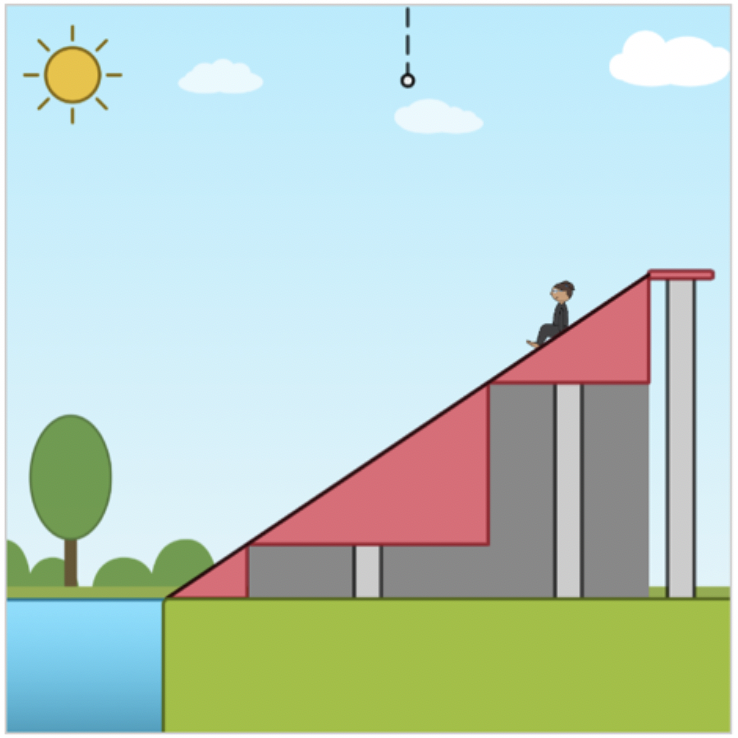

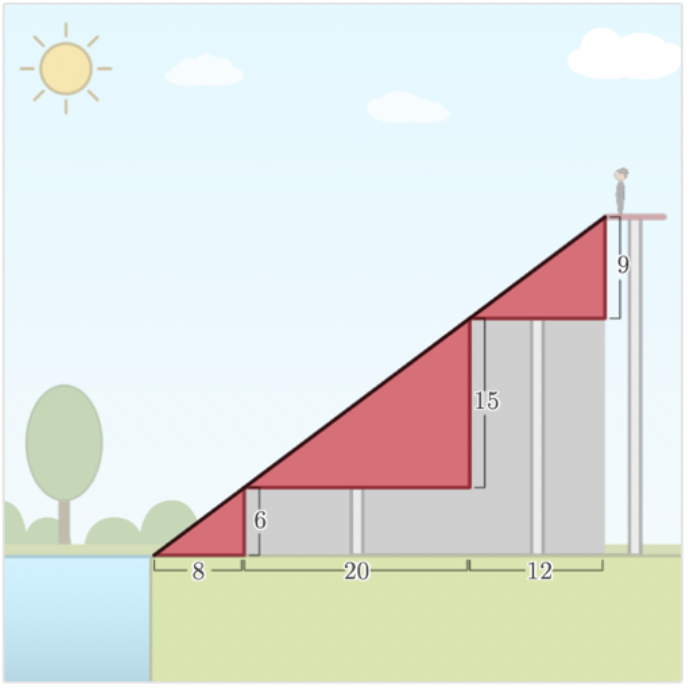

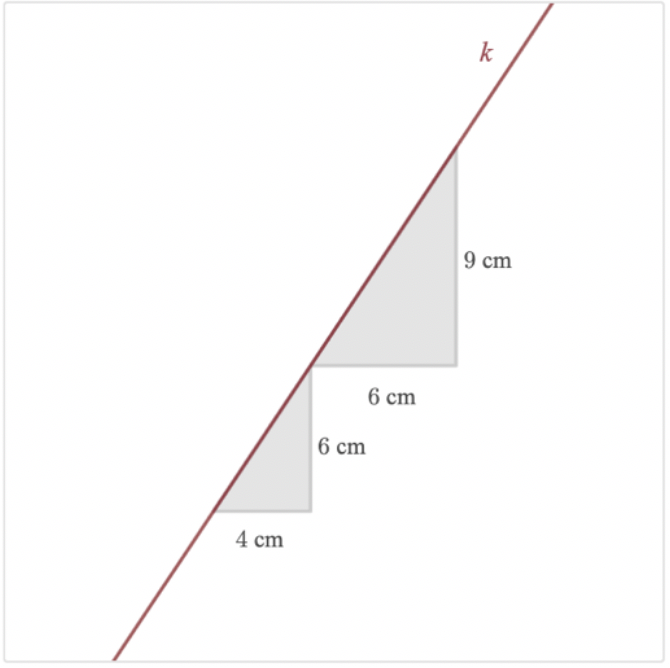

One of the most effective ways to engage students in rigorous thinking is by introducing mathematical conflict: a challenge that disrupts student expectations and forces them to think critically. When students encounter something that doesn’t immediately make sense, they are more likely to engage deeply in the problem-solving process.

How Do We Create Mathematical Conflict?

- Break something – introduce a change that breaks an established rule or expectation for students (Do the angles of a triangle always sum to 180 degrees? What about in non-Euclidan geometry?)

- Present problems with multiple solutions – Instead of asking for a single answer, design problems where students must justify different possible responses.

- Use open-ended tasks – Remove rigid steps and instead allow students to explore different pathways to a solution.

- Introduce missing or ambiguous information – When students don’t have all the details, they must use reasoning and estimation to fill in the gaps.

For example, in Desmos Classroom, there’s an activity where a ruler is shown with a missing section. Students must figure out how to determine the missing measurement using only the numbers they see. This subtle shift—from simply subtracting two numbers to thinking about how subtraction works—adds depth to the task.

2. Building Meaningful Connections

Math shouldn’t exist in isolation; it should be connected to the world students live in. When students see how mathematical ideas apply to real-life situations, they engage more deeply.

How Do We Build Connections?

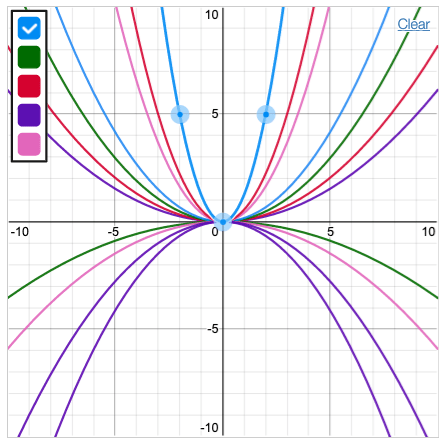

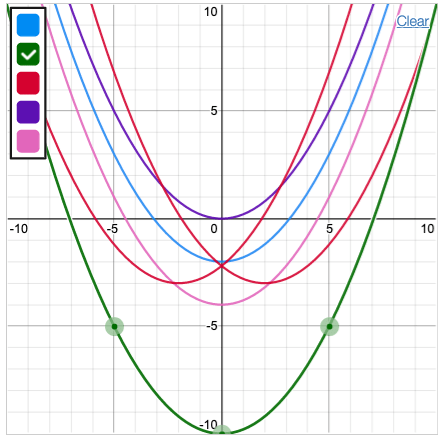

- Encourage the “What if?” mindset – Push students to think beyond the given problem by modifying conditions and predicting outcomes.

- Use contexts that spark curiosity – Introduce scenarios where students must explore mathematical ideas naturally, rather than through rote exercises.

- Let students take ownership – Provide opportunities for students to explore different mathematical relationships and make choices in how they solve problems.

Consider an elementary multiplication task. Instead of just providing two numbers to multiply, imagine giving students a hamster home design challenge. They must decide how long the tube connecting the homes should be and use multiplication factors to find the right length to complete the home. This simple shift transforms multiplication from an abstract operation into a meaningful decision-making process.

When students make real-world connections, math stops being a set of steps to follow and instead becomes a tool for exploration and reasoning.

3. Empowering Students as Mathematical Creators

Perhaps the most powerful way to foster rigor is by shifting students from passive learners to active creators. When students create their own problems, scenarios, or solutions, they are naturally pushed into deeper mathematical thinking.

How Do We Let Students Be Creators?

- Encourage student-designed challenges – Have students create their own math problems for classmates to solve.

- Use technology to amplify student creativity – Digital tools like Desmos Classroom allow students to design and experiment with mathematical models.

- Facilitate class galleries and peer discussions – Let students showcase their work and engage in mathematical discourse.

A great example of this in action is a classroom challenge creator—a space where students generate their own problems based on concepts they’re learning. Not only does this reinforce their understanding, but it also develops their mathematical identity. Instead of seeing math as something teachers give them, students begin to see themselves as doers and thinkers of mathematics.

Rigor Is More Than Just Harder Problems

Rigor in math isn’t about making numbers bigger or computations more difficult—it’s about creating opportunities for deep thinking. We can achieve this by:

✔️ Creating mathematical conflict that challenges students’ thinking (break something!).

✔️ Building meaningful connections that make math relevant and engaging.

✔️ Empowering students as mathematical creators who explore and design their own solutions.

When students experience math in these ways, they don’t just learn procedures, they develop a deep, lasting understanding of mathematical concepts. And most importantly, they come to see themselves as capable, confident mathematicians.

Let’s redefine rigor, not as difficulty for difficulty’s sake, but as a means to create thinkers, problem-solvers, and creators of mathematics.